Today’s young club DJs – and those honing their skills at home with a DJ controller and laptop – don’t know how easy they have it compared to the trailblazers of the 1980s.

A DJ controller and the right app make it almost effortless for anyone to mix one track into another. The software calculates the beats per minute (BPM) of the track, displays the song’s key, and can be used to adjust any track to match the tempo and key of the previous one. And that’s just the basics.

I use the same gear myself, a budget Numark unit, for when I go digital crate-diving to create a mix of some old favourites. I’ll happily lose an afternoon beat-mixing, sampling, and scratching (yes, the rash is getting better).

Back in the early ’80s the best a club DJ like yours truly could hope for were a couple of belt-driven turntables with fixed speeds of 33 or 45 RPM.

Few club managers saw the value in investing in the new-fangled Technics SL-1200s, with their instant start and pitch-control sliders to adjust the speed.

But after a few years of being a hobby mobile DJ, landing a club residency was joy enough – I didn’t much care what turntables were in the booth.

My days of loading the car up with tonnes of gear, Citronic disco console, speakers, stands, light gantries, a smoke machine, and box upon box of vinyl, were over (no more weddings!). Now all I had to carry were two boxes of records, a microphone, and one surviving cup from a broken pair of headphones.

The music I played in clubs was miles away from what radio stations were spinning at the time. Pop and rock dominated the airwaves, as programme controllers across the UK assumed dance music was a passing fad.

Sure, there were specialist shows that featured club music, but that was about it. Because mainstream radio didn’t cater to club culture the pirates stepped in to fill the gap – but that’s a whole other story.

In 1981, while radio stations played Shakin’ Stevens, Bucks Fizz, and Julio Iglesia, we “serious” club jocks were spinning the tracks the stations ignored:

- Kleeer – Get Tough

- Yarbrough & Peoples – Don’t Stop the Music

- Arthur Adams – You Got the Floor

- Carl Carlton – She’s a Bad Mama Jama

- New York Skyy – Call Me

- Beggar & Co – (Somebody) Help Me Out

- Rick James – Give It to Me Baby

- Young & Company – I Like (What You’re Doing to Me)

- Sharon Redd – Can You Handle It?

- Freeez – Southern Freeez

- Joe Sample – Burning Up the Carnival

Some of these eventually made the pop charts but we played them first, club goers bought them because they danced to them.

I was happy working the clubs and did a decent job keeping the dance floor busy…Then everything changed.

I was sitting with then-DJ Paul McKenna when he casually beat-mixed one track into another at Radio Top Shop, London. I’d never heard anyone blend records like that, it was seamless.

I started listening more closely to the tracks I played, figuring out which ones would play nice together. I began pre-planning my sets with far more care – I lifted my game.

Helping me along was the rising use of digital drum machines, delivering a solid fixed beat – unlike drummers who’d naturally drift in and out of time – making beat mixing harder.

The overall sound was changing too, with keyboards and synths edging out guitars, and sampling featuring in house music (Gilbert O’Sullivan stopped the sampling free-for-all in the ‘90s).

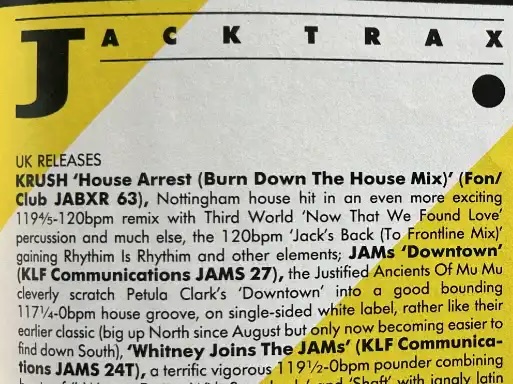

But beat-mixing with analogue turntables took work. First, you had to find the BPM of each track, either by using a stopwatch to count the number of beats in 60 seconds, or hoping someone else had done it for you (James Hamilton comes to mind).

I’d stick a label on each record sleeve noting its BPM along with a list of other tracks it would work well with, worrying about the key of a song didn’t enter my mind until much later when I started recording mixes at home.

Initially I’d simply use the instrumental “donut” of a track, when the song dropped to just the beat for a few bars, as a mixing point. Unlike today, there was no way to loop a bar or two, there was no ‘get out of jail’ button to press to buy time if a mix wasn’t working.

As some point record labels realised the power of club DJs to break new music, knew we liked to remix the hits, and began releasing alternative mixes, instrumentals, elements of the tracks, and even giving us a cappella versions. They were often released as non-commercial white labels sent to select DJs.

It was the isolated vocal of 1985’s Trapped by Colonel Abrams that first gave me the idea to drop the vocal of his track over the beat of another. Doing that in front of 2,000 people with two fixed-speed turntables was terrifying – but it worked. Club goers were dancing to the beat of one song but listening to the lyrics of another. Easy to do today.

Later, I bought a Yamaha keyboard sampler and could copy a snippet from a record and play it over another in the style of Natalie Cole’s version of Pink Cadillac. DJ turns musician.

No software, no computers. Digital gear was emerging, but DJing was still analogue. Mixing tracks and keeping them in sync was an art that had to be learned, practised, rehearsed, and perfected before you walked into the club.

Looking back, I reckon my old Citronic disco unit cost around £600 / AU$1,200 in 1978. Today, a basic DJ controller starts at around AU$300, plenty enough to get you going.

While much of the skill of the analogue DJ has been lost with the rise of digital controllers, they’ve also led to new skills being developed and made DJing, beat-mixing, and remixing accessible to anybody who wants to have a crack at it.

Back in the day I had to use turntables, a mixing desk, a reel to reel tape machine, razor blade, and splicing tape to create sequence mixes. That gear would have cost £5,000-plus. You had to REALLY want to do it.

And thanks to DJ music libraries there’s no need to spend every penny on vinyl, which in itself takes some of the magic away of finding music. How many of us put a white label over a new track so nosey DJs on a night out couldn’t see what it was? Have we lost something by everything being available all the time?

However, sharing our mixes is also a lot easier. Gone are cassette tapes (sold for a fiver down the pub), and in are platforms such as Mixcloud that provide a legal way to share mixes and radio shows.

Boy, it is easier today, isn’t it? And it’s still great fun – no matter your age.